Psycholonials

*Addendum: Since I originally wrote this, Vivziepop released a pilot for a potential Homestuck show. It's good!*

It is now. You begin reading an article about Psycholonials, though you barely know what that is. You are strangely apprehensive, although you cannot say what it is you apprehend.

It is May 2020, three months into Covid. You are Z, and lockdown has driven you mad. But even though you are Z, you observe her/them/xim/yourself from the outside, dissociating, watching yourself on a screen.

Z is—you are—in despair. She had a mental breakdown, survived cancellation, and yearns to resurrect her online social status. They are unemployed. You haven't seen a friend in months. Z posts updates for a handful of followers, doomscrolls through the news, eats week-old Macaroni, downs shots of whiskey upon waking up mid-afternoon, harasses one of her few online followers, vomits in said macaroni, dissociates, remembers her unfinished manifesto about Clowns. This can't go on. You must leave this hole and see your friend. While driving there, drunk, a cop pulls her over. The cop shoots the manifesto. Z kills him and steals his cop car, driving it into the sea.

We all lost our minds during Covid. We spread conspiracies, made sourdough, became alcoholics, spent every waking second online. In my madness, I wrote 65,000 words about a webcomic called Homestuck, one of the internet era's defining literary works (I say half facetiously, half sincere). Homestuck was written by Andrew Hussie, never a paragon of sanity himself. In his Covid madness, Andrew Hussie made this.

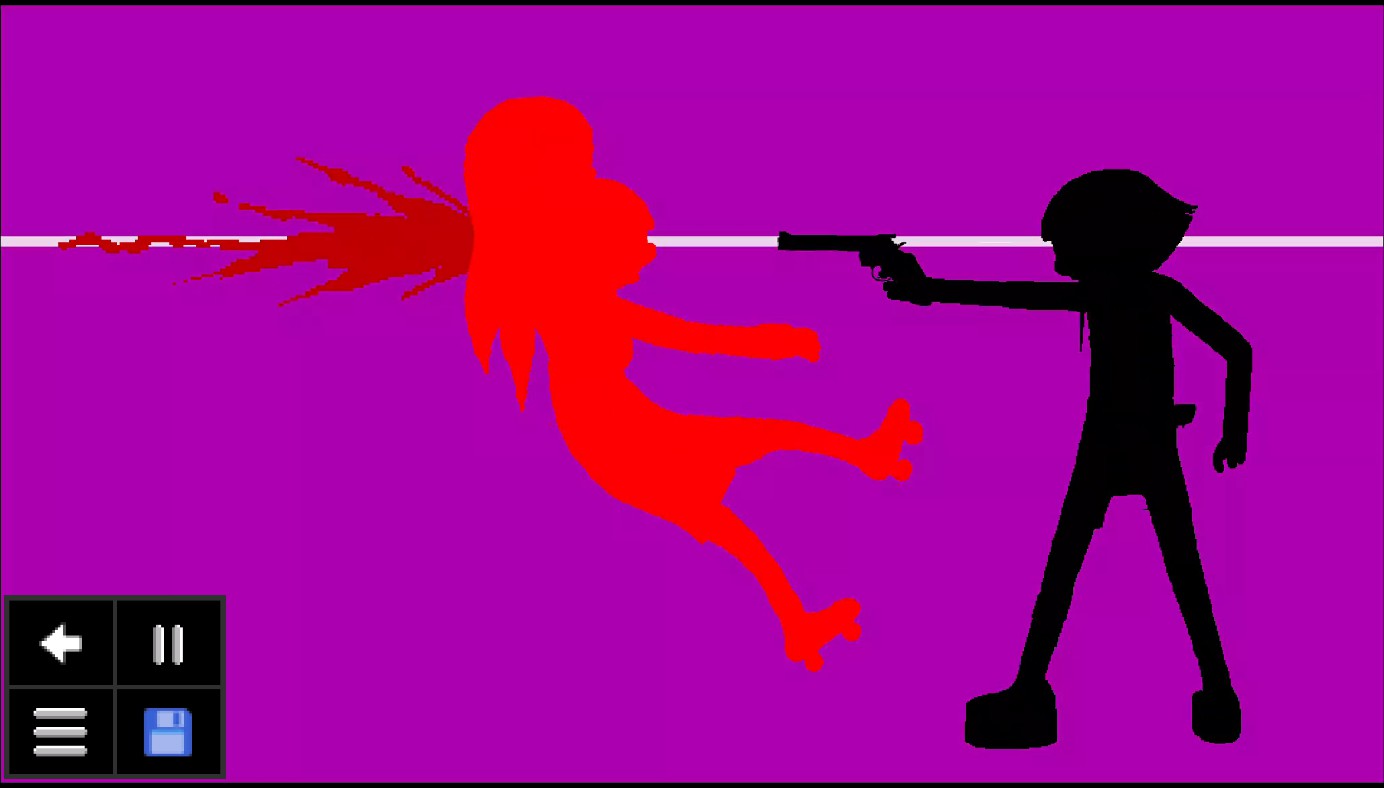

Psycholonials is a mess. I mean, look at it. It has a thousand reviews on Steam—respectable for an indie experiment, shockingly little considering Hussie's pedigree and the fact it's now free. But its mess is compelling. There's a delightful slow burn to the storytelling, epitomized by Z's oblique references to "nightmare people" and "the incident". The second-person narration makes it visceral. The pseudo comic panel structure creates a sense of start/stop momentum. Hussie is a master at capturing the rhythms of online communication. You feel the time between texts. You feel the brief thrill as the simulacrum blots out the world. But when Z puts down their phone, the background music cuts out, the shadow-play stops, and you find yourself back in the desolate cave. In my view, this is the defining tone poem of Covid. Sorry, Inside.

You—Z—hang with Abby in her billionaire parents' house while they're away. You relax on luxurious furniture, drink million dollar bottles of wine, scam her parents out of money over the phone. You explain that your manifesto is about radical left wing politics and gender, as well as Clowns. You define a two dimensional gender matrix and declare yourself anarchic Clown Gender. One night, drunk on revolutionary fervor and opulent wine and the thrill of human connection, you kiss. But you—Z—regret it. One of you will get hurt.

The contrast between the despair of the first chapter and the warmth of the second is delightful, almost delightful enough to hide the obvious question: Wait, clowns? Is this written from the left? This is a cruel parody of progressives, the kind of thing Ben Shapiro would write. You, the characters, are among the most privileged people on earth. Abby's the child of billionaires. Z doesn't work and lives alone, but never frets about rent for their place in Nantucket (median house price: $4.5 Million). Abby and Z, convinced life is hard under Capitalism, aspire to be influencers, never working a day in their lives. Insulated from hardship, they mooch off of others, invent nonsense genders, kill the police, and nonsensically rant about Clowns. And thus you (not Z) ask, is this aspirational, or is this a vicious critique?

Yes, and no. This story centers an overt and familiar critique of the left: we collapse into infighting. The People's Front of Judea hate the Judean People's Front, but forget they hate Rome. Who needs the Right? The Left destroys itself.

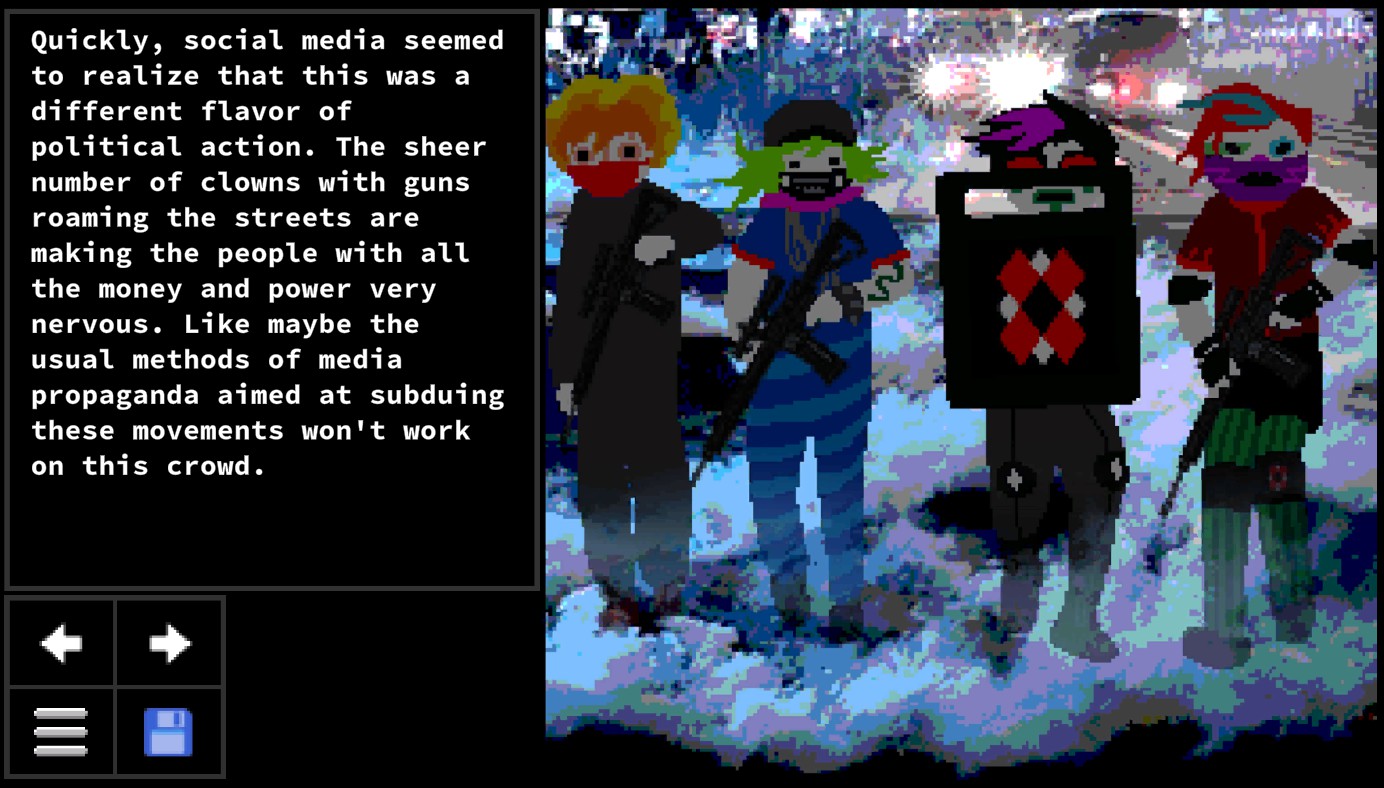

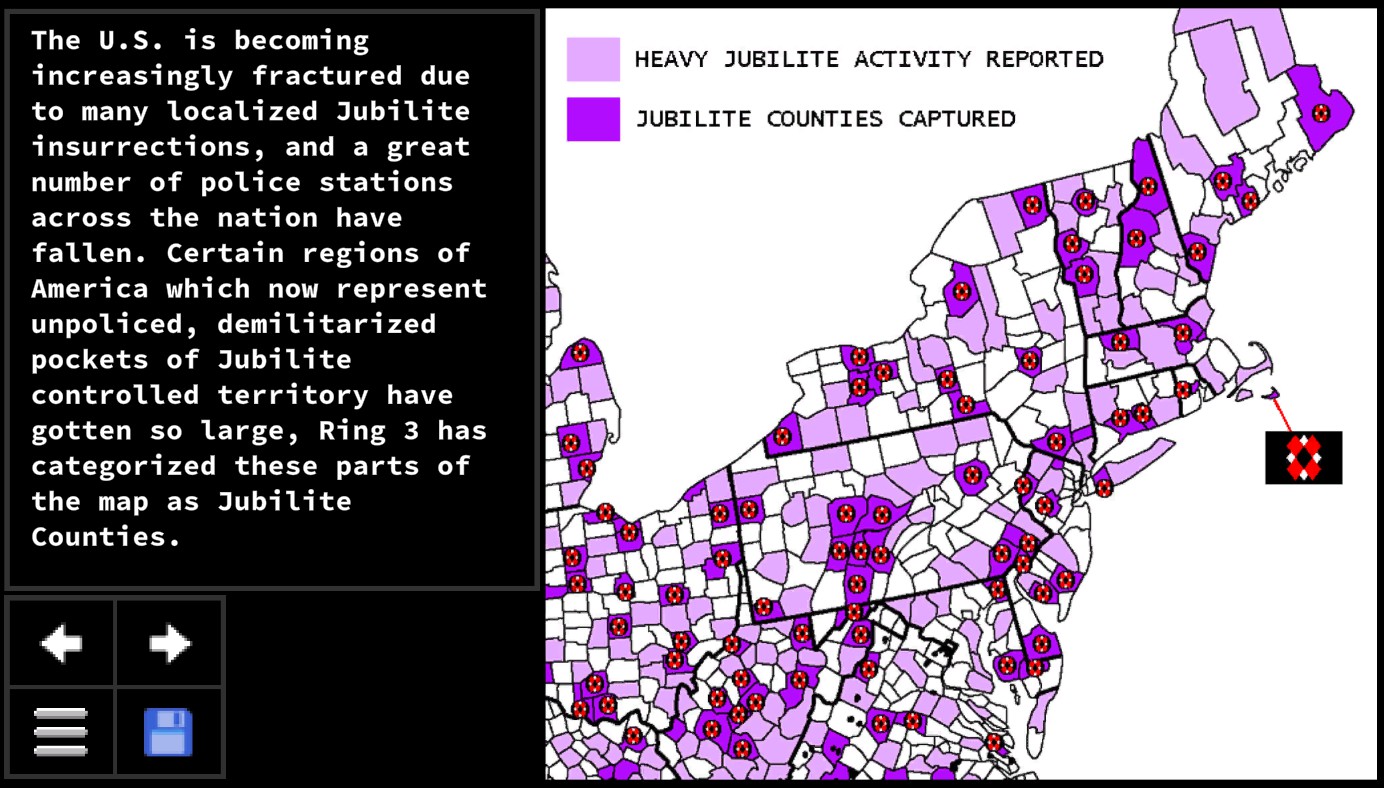

And yet, Psycholonials is also Left fantasy, indulgent beyond Trotsky's red dreams. Z's manifesto takes off. Their followers—Jubilites—converge on Nantucket, dressed as clowns, armed with assault weapons. (This alone is wish fulfillment. Most progressives I know are afraid to buy groceries; have you ever met a leftist with a gun?) George Floyd protests take the country by storm, and the Jubilites harness this energy, leading to a shootout between clowns and cops. The clowns stage a fake biochemical attack to force people off Nantucket, then take over the island, renaming it Whimsiphae. This begins a tense standoff with the US, but celebrities like Post Malone and BTS join the Jubilite cause. The movement spreads internationally, the clowns take over companies like Facebook from the inside, and you look at the time. Now. You've spent how long reading this review, and there are how many words left? Is this a good use of your time? This is what you apprehended; a dumb game you've never heard of has a dumb plot. Or, is this is a game? You're not sure. Either way, you don't care about Whimsiphae. Nor do I. But if this is so dumb, why am I writing about it after five years? Why do I care? Why should you?

Let's back up. Let us talk about Clowns.

Clown Semiotics

The clown is a modern take on classic archetypes: The Fool and his cousin The Trickster. Scholar Faye Ran defines the Fool around five traits: He is Idiosyncratic, Maladapted, Marginal, Dual, and Comedic. Fools do not fit within society's bounds. The Tarot's Fool is not numbered among the arcana. In playing cards, a Joker has no suit. A clown does not look or act like us. He cannot hold a steady job or go to the bank, unless it's some sort of silly bank, for clowns.

This does not mean the rest of us, non-clowns, find adaptation straightforward. Plato knew we steer two horses, one rational and one indulgent. Darwin found that we are animals at heart. Freud probed at the tension between our frenzied lusts and need for social cages to hold those lusts in check. Nietszsche recognized the pull between Apollonian order and Dionysian chaos. Derrida saw ideas defined by their opposites' trace—the profane defines the sacred, the chaotic the ordered, the transgression the norm. Jung linked the Trickster archetype to the shadows we suppress and the liminal spaces of carnivals—where Dionysus takes over, masters serve slaves, and wine and phalli flow. Aristotle, writing on comedy, praised the uproarious mirth (γέλως) of a philosopher (φιλόσοφος) hit with a pie (πλᾰκοῦς). Wittgenstein liked clowns, I think.

A clown's anarchy is cathartic. He discards inhibitions, embraces chaos, transgresses the boundaries we wish to but cannot. This is possible because he is ostracized: the king's fool insults him because, unlike noblemen, he has no status to lose. But while we seek catharsis, society must carry on. The fool must be punished for transgressing, laid low by his japes, subjected to mockery and disdain. Calling someone a clown is not a neutral description, but an insult. To laugh at a clown is to shame him. As Mr. T recognized, a Fool's a pitiful thing.

Z is maladapted and marginalized. She does not work. She scarcely leaves her room. The internet canceled her and Covid shut her away. Cast off from Apollo, she drinks deep from the Dionysian well. She is aware of the parasocial boundary between creators and fans. She knows she will regret the transgression. And yet, she gives in to her instincts and lays a "cunning thirst trap", ensnaring a follower with animal lusts to humiliate him. Her cruelty offers brief catharsis, but soon Z herself is humiliated, unable to indulge even their base need to eat, because xie threw up in xier food.

This transgression and concomitant punishment sets the story in motion, prompting Z to dissociate and revive their manifesto. It's when Z understands that she is—that you are—The Fool.

A clown's chief tool is the joke, a disarming way to juxtapose ideas, which at first appears wrong yet illuminates something profound. Consider a joke from a popsicle stick: "What's a cow's favorite activity"? To graze? To lick salt? As the sweet melts away, you uncover the answer at last: "Watching moo-vies!" Hesitation gives way to revelation, then delight. Like a zen koan, surprise prompts satori. The connection is not biological, but linguistic. Movie abbreviates "moving picture". Its cousin Cinema is from French cinéma, from Greek kinema—"motion". And yet, though these words share both meaning and root, they do not share function. There is no joke in cows watching cinéma (though perhaps ciné-moo?). Wittgenstein, in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, held that words were mere labels for objects, sentences pictures of reality, statements like "cows enjoy moo-vies" maps of logical functions and facts. But this joke is not to be confirmed or refuted empirically. We need not observe cows watching Moo-nstruck or In The Moo-d for Love or Moo Dinner with Andre or Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles or some ridiculous recut of Raging Bull, with cows. No, as Wittgenstein's greatest critic (also Wittgenstein) observed, we must decouple the map of language from the territory it claims to represent. This joke is disarming, forcing us to grapple with the ways we interpret the world through a glass darkly, laying bare how our understanding is filtered through language which predates us and is necessarily collective. We are trapped in Plato's cave, watching moo-vies on its walls.

Not all jokes can be this sophisticated. Some merely explore and challenge society's taboos. As we draw our maps of dimly glimpsed territory, we divide the world into categories, but these boundaries are always imperfect. It's uncomfortable to admit the world was not made for us.

In Judaism, pigs (split-toed mammals that don't chew cud) and lobsters (undersea bugs) are "abominations"—grotesque category errors. Today, most of us eat pigs but wouldn't dream of eating dogs, not because of holy scripture or nuanced theory, but because Livestock is a different category than Pet. To ask whether it's unethical to eat dog is itself a category error—it's wrong. It's wrong even to talk about. Telling someone not to eat a dog is insulting. Asking why you can't serve one for dinner marks you a madman. And yet the very fact that these taboos differ across cultures reveals that they are, for all their power, arbitrary.

If we can't discuss taboos, how do we learn them? How do we push against taboos that need to change? The Fool, himself a transgressive character on society's fringe, is our guide. Seeing someone overstep the line illuminates where that line is, and mockery can be a permission structure for empathy; the core texts of gay liberation included The Birdcage and Will and Grace. However, even the Fool must be careful. A clown may joke about eating a dog, but he cannot eat a dog on stage. He could not turn his act into a Benihana-style show where he grills the dog in front of you, nor present a Michelin starred 37 course dog tasting menu (all 37 fitting snugly in a comically small bowl), introduced with a molecular gastronomy amuse bouche where the dog's snout has become cotton candy, paired with wine the sommelier loads into seltzer bottles and sprays in your face. No, transcendently delicious though this may be, it would be in poor taste. There are limits to how far a clown may transgress.

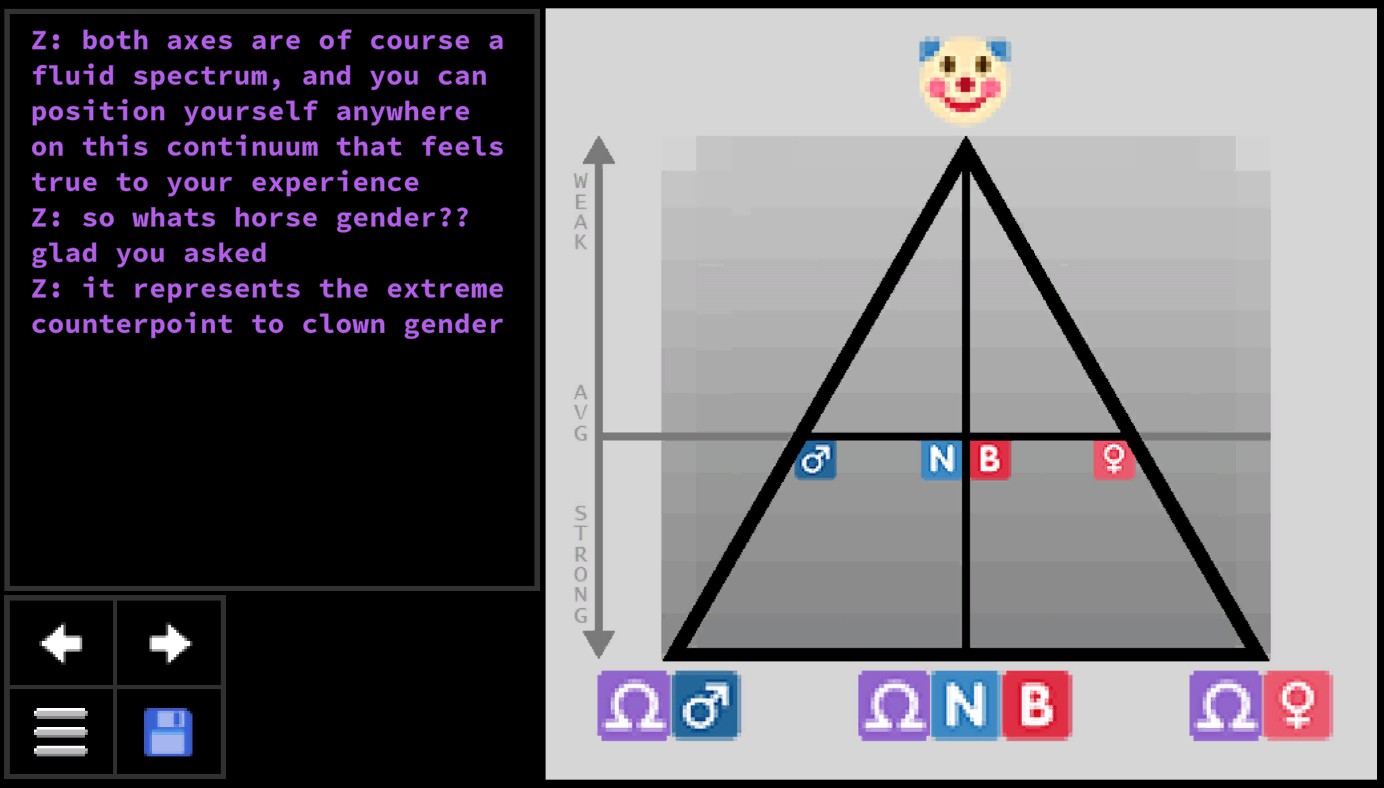

Queer audiences are on guard against people who aim to humiliate. Humor itself is no defense; we resist Ricky Gervais' "jest" that he identifies as a chimp. Z is no Netflix celebrity. She is marginalized, million dollar wine bottles aside. Their joke begins with one axis defining a spectrum from male to female. The baseline assumption—the premise—is that gender is a spectrum, nonbinary is part of that spectrum, and that you self-identify where you fall. This is how we know this is not an attack helicopter joke. Z works within our framework. We can lower our guard.

The joke is that in Z's philosophy, this is not one axis, but a 2-dimensional gender plane. The X axis is Male vs Female. The Y axis is Clown vs Horse.

Toward Clown is gender anarchy, toward Horse is confident gender euphoria. This axis could be hot/cold or strong/weak, but the surprise of these labels slaps you into satori. The dyad itself—the opposite of Clown is not sober businessman, but Horse—prompts us to redefine clown in terms of its opposite; a clown is not merely a joker, but the opposite of the majestic, steadfast horse. More surprising, the axes are not orthogonal: move toward Clown and the divides between Male and Female collapse, but move toward Horse and they amplify. Nonbinary may be its own deeply meaningful category, or a way to reject categorization. The game cites J.K. Rowling as Horse Female; she is emphatically a Woman, defining her womanhood in violent opposition to what she's not. But Abby is also a Horse Girl, not out of hatred but comfort in a gender role that fits her like a glove. The game uses Obama as the canonical Horse Man, but that seems wrong to me; it should clearly be Andrew Tate Bojack.

This is useful language and, in my view, insight. It's a rich joke that rewards, nay (neigh?) demands engagement. I have drawn this graph on fridges to explain my own gender. To me, this resonates. But crucially, it's pre-marginalized and therefore safe. I can say "There's a stupid graph in this dumb game nobody played". If it resonates, then perhaps, like Z and Andrew Hussie themselves, you will call yourself Clown Gender, accept whatever pronouns people care to use, and join my dating app Clowndr. (Yes, I know my competitor Laughdr has the better name. But do they let you match with partners based on the cosine similarity of your genders? No.) If it doesn't resonate, don't fret, it's just a joke.

But if a clown can enlighten, there's a thin line between transgression which delights and transgression which terrifies. A clown is liberating on the other side of the stage. But if a clown blurs the line between sacred and profane, a loose clown tells us nothing is sacred. If a clown is Other—suppressed chaos at odds with society—then a clown outside his context is a threat. A clown's makeup is uncanny, distorting its face. The look of this game is also uncanny. It's off-putting. It's wrong.

As Z's influence grows, she repeats her first transgression. She summons Percy—the fan she tormented—to her island.

Z turned down Abby's advances because her sexuality is a weapon, and Z didn't want to hurt Abby or zirself. But now she turns that weapon against Percy, seducing him with blood streaming down their face, giving him a clown nose, enlisting him to die.

Z has completed their metamorphosis from restrained, pathetic Fool to unrestrained threat. The barrier has been destroyed. In Percy's terror, you recognize yourself. You are not, in fact, Z. You never were. Z's choices were never yours to make.

It is unnerving when the medium talks back. It is now.

At last, we see these clowns from the outside. We realize we are not them. Percy—We—will die, and Z will find herself caring. She is not as heartless as she pretends to be, just as they were not as glamorous as they pretended to be. But that's cold comfort to Percy—to You.

Is this why I like this game? Do I just want to be violently seduced by a terrifying genderless clown?

Yes.

Failures

Psycholonials should have ended here. After the graphs, Clown Gender barely comes up; no homophobia or coulrophobia stands between Abby and Z. The tools of the Jubilites are the tools of any militia. Their terror is not the implicit threat of a Fool unconstrained, but the blunt, explicit threat of guns. Their weaponized pranks ("pranxis") lack the cleverness of Abbie Hoffman throwing dollar bills into the stock exchange. The main prank we see is scamming Abby's parents by… giving misleading advice about Bitcoin? Whimshiphae's main export is Weed, a one-dimensional joke which lacks either plausibility or juxtaposition. The clowns should surprise us by selling either balloon animals or insurance, or at least give their cannabis political weight (have the bourgeoisie ever, like, really looked at a Clown?). The Fool is Idiosyncratic, Maladapted, Marginal, Dual, and Comedic, but Z stops being a marginal figure as their revolution takes hold, adapts too easily to the new world, and rarely tells a joke. Has Z even read Paul Bouissac's The Semiotics of Clowns and Clowning: Rituals of Transgression and the Theory of Laughter? Have respect for the craft.

If the Jubilites are poor clowns, they are also poor Leftists. Z may have read the title of Mikhail Bakunin's It Would Be Cool If Someone Overthrew The Government While Dressed As A Clown, but surely not its text, which is more nuanced. There is no Jubilite political economy, no labor theory of mirth, no chart of Clown Proletariat and Horse Bourgeoisie. Z never considers giving their million dollar wine to the poor. Z lambasts America for failing to protect its people from Covid, but leads no whimsical quarantine. Her followers never wear masks. Abby criticizes Z for not thinking through the aftermath of revolution, but may as well direct that critique toward Hussie himself.

Z rallies her followers by claiming "We will replace this vile, corrupt, imperialistic farce known as American democracy, and replace it with a mode of governance that is not intrisically (sic) predicated on centuries of terror and genocide, and one that instead meets every need of its people without excuse or compromise." Of course, Whimsiphae is predicated on terror and violence; the clowns themselves look over their shoulders at all times. But why bother? To treat this as a political platform worth refuting is to condescend.

The revolution comes through time skips and info dumps, leaving the story an indulgent fan wiki recap of itself. Unable to commit to clown semiotics or political critique, it mires itself in logistics about how they supply power, how the Bitcoin scam works, how clowns get to the island... none of which matters. To find this revolution plausible is to defang any critique of American empire. To accept the fantasy is to render logistics redundant. The point, of course, is that the real obstacles come from within. The game's overt criticism—the left is a circular firing squad—is safe. It implies our external enemies are irrelevant, and we'd be unstoppable if we just reached consensus. We just need more meetings.

But Whimsiphae's firing squad is not based on ideology or factions. Z learns that her right hand follower, Joculine, previously led Z's cancellation. In response, Z kills her. She was vital to Z's project. She was down with the clown. But Z doesn't care; she wants blood.

If this revolution is based on so little, what entices BTS to join the clowns? By all accounts, the answer is Aesthetics. Z spreads her movement on Instagram, a platform all about shallow appearance. Her followers are drawn to the signifiers of leftism (Che Guevara, Molotovs, guillotines) and the permission structure to be cruel (cancellation, purity tests, guillotines). The ideology and political platforms are fig leaves. The implications of this critique cut deeper: Why did the left flame out after 2020? It was merely a fashion trend.

This is a provocative critique, especially for a game aimed at the Left. Yet it's not clear the game understands what it's saying, and it pairs strangely with such indulgent fantasies of success. The back half of this story is a mess, unsatisfying however you read it. Perhaps the confusion is understandable when you remember this fantasy did not come from the trodden underclass; Andrew Hussie's a millionaire.

Andrew Hussie

Andrew Hussie's an outsider artist, one minuscule step closer to normal than Henry Darger. Yet through talent, absurd work ethic, and a deep understanding of the internet, Hussie created a brand—Homestuck—from nothing. He taught countless teenagers to cover themselves in grey paint and say "moirail" instead of best friend. He helped nurture Toby Fox, who made Undertale in his basement. He sold Homestuck's publishing rights to Viz Media, who got the comic in physical bookstores. He launched a Kickstarter to form a business making Homestuck video games, raising $2.5 Million.

In retrospect, the Kickstarter is nothing but red flags. The promotional trailer is just contextless Homestuck clips; there's no vision for what he wants to make. In any case, would you give Thomas Pynchon a small business loan? But we trusted Hussie, because Homestuck earned our trust.

Homestuck is hard to recommend. It's a massive commitment that takes a thousand pages to get going. A group of literature professors from the world's top universities unanimously agreed it's the most poorly paced work of fiction ever made. One of them gouged out his eyes. But it's also a work of genius, a bold adaptation of comics and novels for the internet. It's the most audacious and inventive work I've ever read.

In 2011, Jennifer Egan won a Pulitzer for her "post-postmodern" novel A Visit From The Goon Squad, which incorporated text speak and powerpoint slides. Contemporaneously, Andrew Hussie had an interdimensional demon take over his comic, giving commentary on its events, telling one story in the panels and another in the website's header, letting you leaf through his scrapbook to see fragments of vignettes, one of which involved two afterlives bleeding together to enable a posthumous romantic connection between two now-dead characters who in life had only met through text, and whose love story, beautiful in the moment, can't last (mortal coils aside), yet who forge a brief but meaningful connection despite that, giving each other tours of their memories which manifest as reified dying dreams. Hussie desperately needs an editor, but if he wanted it badly enough, I firmly believe he could win a Pulitzer as well.

Instead, his dream crashed. His $2.5 million game studio was horrifically mismanaged, the money all but burned. A decade later, the game's not close to done. The books stopped coming; I may be the only one who bought them. Nobody liked the comic's ostensible sequel; I wrote 65,000 words about Homestuck but never touched it. The website homestuck.com itself has been abandoned, left to rot. (If you actually want to read the comic, go here. Yes, I know the beginning sucks. I swear it gets good a thousand pages in!)

Even before immolating his brand, Hussie was hard to love. He existed in Homestuck as an obnoxious self insert who proposed to his teenage OC and served as deus ex machina in his own plot. When you make it impossible for your fans to separate artist and art, then present yourself as an asshole, you shouldn't be shocked when they believe you. With the failure of his business, Hussie, the Fool, transgressed. He now inspires the same derision among his fans as George R. R. Martin. His fans aren't just disappointed; they feel betrayed. And with the failure of—and outright disinterest in—Psycholonials, he's been punished.

Psycholonials was not a throwaway experiment. Hussie had it translated into 13 languages. The Pause menu sends players to a merch store that doesn't exist. He clearly had hopes that did not come to pass. Instead, this blog post is the most attention it's received in the last few years. And this humiliation is not undeserved.

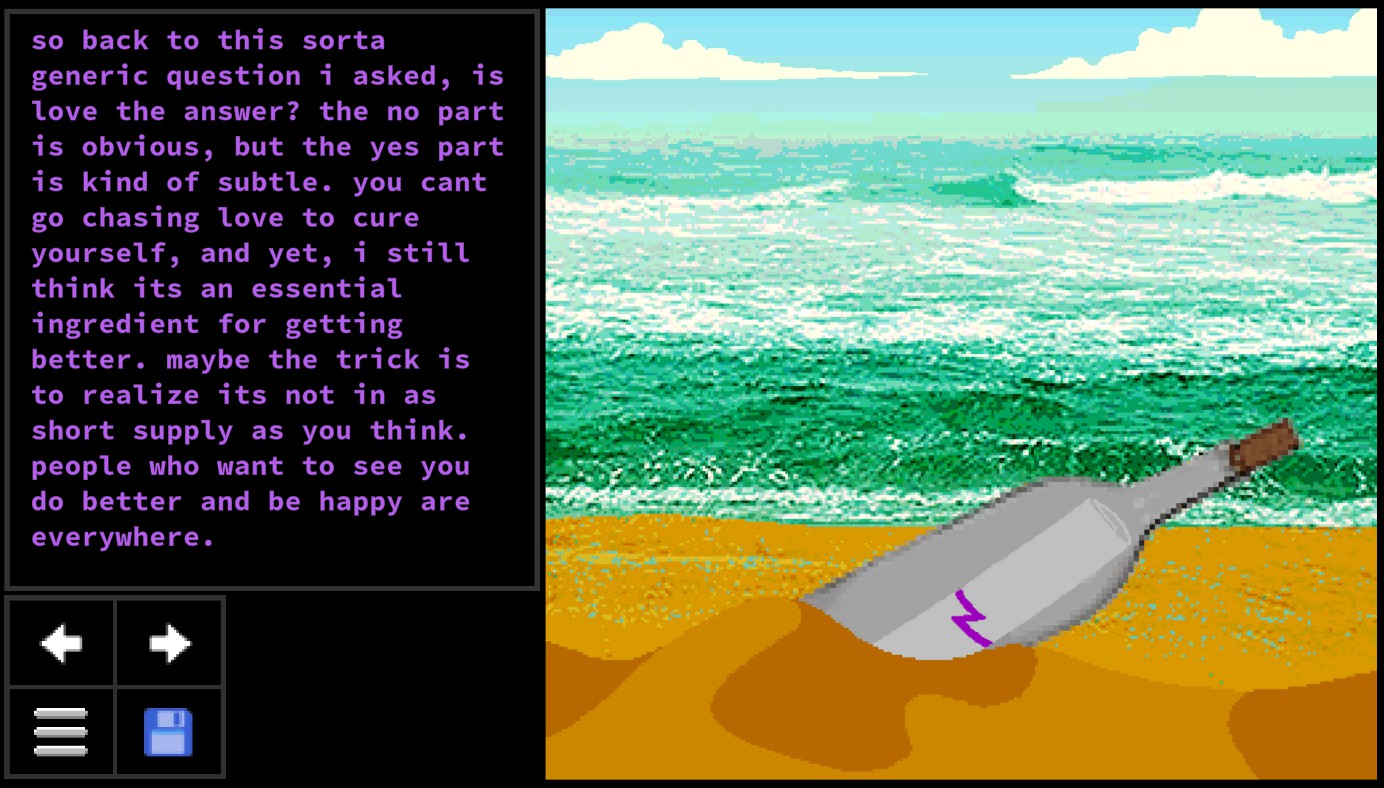

At the end of Psycholonials, written into a corner, Z decides to just... leave. She and Abby flee to Fiji and watch the world burn (why yes, the game does explain the logistics of how she arrives). This is an extraordinary anticlimax, and it's tempting to seek meaning in the frustration like in a Scorsese film, but the game can't linger on the feeling of dissatisfaction for more than a second. Z breaks the fourth wall to talk to you directly, trying to outline their thoughts on social media and revolution and how all you need is love. But she and Hussie adopt the defensive crouch learned on Twitter, knowing this paean to love will be met with a million angry tweets about Gaza or how some people are aromantic or how Hussie is White, so Z endlessly caveats herself and meanders through a dozen meta-thoughts before the game limply ends, exhausted. Like everything else, the ending gestures at compelling ideas that fail to cohere. Whatever this is, it's no punchline.

Hussie has followed Z's lead. Since this game's release, he has found his own exile. He has released nothing else.

Psycholonials is a failure, but it's an admirable failure. It has moments of brilliance. It's thrilling to watch it probe at the medium, forging new paths. It points the way to great works yet unwritten. We, like the Jubilites, must pick up the pieces of this burst of inspiration that fell apart and, likely, was doomed from the start.

Whether or not Andrew Hussie returns, I hope he inspires a new generation of artists to embrace their strange ideas, be bold, and take advantage of new media. Perhaps we can learn from his failures and be inspired by his bravery. I want to read the work of someone who takes up his mantle and follows his lead.

Perhaps that someone is You?

If so, you should start writing. It is now.