Reflections on a Four-Hour City Planning Meeting

I recently moved from Seattle to Kirkland, one of its wealthier suburbs, and was greeted by countless signs like these:

More than a hundred people recently went to Kirkland city hall to discuss whether the city should allow more housing in "transit corridors", i.e. along bus routes. My new home is on one of these corridors, and I was happy to literally say Yes In My Backyard. I went with Livable Kirkland, an Urbanist group supporting the upzone; those blue signs were from Cherish Kirkland, who opposed it (the Kirkland People's Front was unavailable for comment). I want to give Cherish Kirkland the courtesy of believing their stated concerns. It's easy to dismiss both pro- and anti-development arguments as cynical smokescreens; both sides can slander each other as hating the poor (NIMBYs want a gated community to keep out the riff-raff, YIMBYs want to raze poor neighborhoods for luxury condos) or acting out of self-interest (homeowners want their portfolio to rise, renters just want cheaper rent). Assuming the worst leads to madness. Let whoever is without sin give public comment first.

The process is bad, despite everything.

This meeting took place in the evening. There was no time limit; it lasted four hours so that everyone who wanted could speak. Most came in person, but some called in, and some gave written comments in advance. Parents with scheduling conflicts got priority. I'm beyond impressed by how the city tried to make this accessible; for contrast, Seattle hosts meetings in the middle of the day, so people with normal jobs can't attend. But seeing this process organized so well only emphasized its fatal flaws. Less than 0.1% of the city came to the meeting, and this was astronomical turnout; the audience overflowed into hallways and a lower floor. After four hours of comments, the city did not make a decision; they decided to wait a few weeks, until another meeting where we'll have another chance to speak.

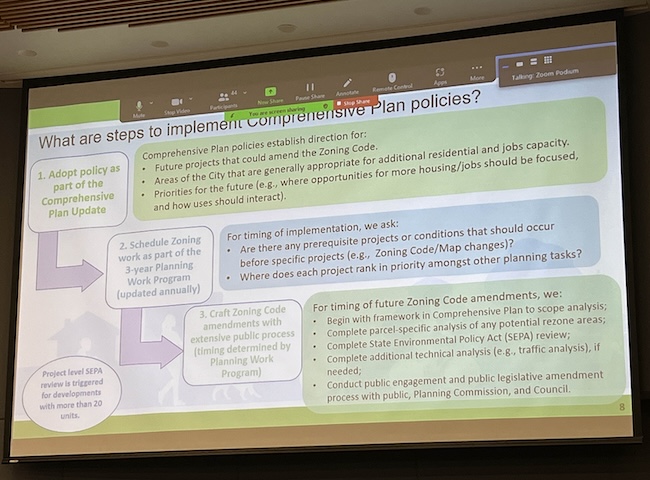

Washington state has great vote-by-mail elections. We have weeks to research the candidates and issues at home, then vote at our leisure for people to sweat the details on our behalf. For some reason, in the context of land use, we reject this Republican process for Athenian Democracy, and most people would rather drink hemlock. I can't blame anyone for opting out of this endurance match, especially when there's no promise of a punchline. How many people had no idea this was happening, didn't want to speak before a hundred people, or wanted to come but worked an evening shift? Most people don't know how local government works, myself included, so the city started with a ten minute presentation explaining what was happening.

This is a clear sign of a bad process. Only sickos like me should spend their evenings watching slideshows about city planning. We need to move away from this process and trust elected officials to plan without micromanagement. In the meantime, we urbanists need to work overtime to ease people into this process, shepherding converts from City Nerd videos into chill meetups then active engagement. I'm glad I went with a group that grabbed drinks afterward. I needed one.

Politics is too local

Overall, speakers were split on the upzones, but the subset who already live in Kirkland were not. Members of Cherish Kirkland emphasized their connections to the city, encouraging deference to its residents and voters. A school principal mourned the difficulty of retaining great teachers, who are so priced out they commute from an hour away. She was bookended by countless speeches which proudly began "As a resident..."

Personally, I side with the teachers, but I don't need to win re-election. Unfortunately, it does make sense for city officials to listen most closely to the people who pay their salaries and can fire them; the exurban teachers can speak, but not vote. This is another problem with the process, and it crystalizes why so much housing policy has been done in state houses. Not only can more people vote for an outcome, but the question "Should we let more people live near the best jobs with the highest salaries?" gets easier the more you zoom out.

"Affordable for who(m)?"

I don't think Cherish Kirkland hate teachers, maniacally cackling as they consign them to endless commutes. Some may consciously trade teacher commutes for neighborhood character, but I also heard immense skepticism that upzoning transit characters would help. This skepticism was ubiquitous in Seattle: New development will just be luxury condos for tech workers, if they're not kept vacant by investors. To build them, we'll demolish whatever few cheap houses still survive. Developers will profit, people will be displaced, and maybe, maybe, some tech bro's rent will drop from $3,000 to $2,900. Here, I heard countless variations of "Kirkland will never be affordable". These arguments might reject basic tenets of supply and demand, but they might simply submit to the scale of the shortage. Say these upzones lower prices 10%: could any teachers priced out of $1.5 Million houses buy at $1,350,000?

Some of this is a collective action problem: upzoning transit corridors in Kirkland won't solve everything, but upzoning The Suburbs™ will. That's a hard case to make one city planning meeting at a time, and another reason for state action. Some is learned helplessness about housing in general. This will hopefully get easier as YIMBYs win more successes elsewhere, but right now it's too easy to nitpick specifics, like saying Texas' low rents are just because of sprawl.

I also see a need to bypass this skepticism by treating new development as beneficial in itself, not a sacrifice for someone else's rent. In Seattle, I'd say that new luxury units mean tech bros don't need to kick you out and live in your house instead, that new development raises revenue for city services, and that more people support more amenities (a new NBA team?). I don't know what the suburban version of this looks like: maybe an appeal that kids and grandkids might actually live nearby?

The Transit-Driven Catch-22

I heard two objections to transit corridors:

1) Kirkland doesn't control its bus service; King County Metro does. The country has cut service since COVID, and they could scrap the bus system tomorrow. Why plan around a bus we can't control?

2) The bus service isn't good or frequent enough. Anyone on a "transit corridor" will still be car dependent, so the premise is flawed.

These objections are a Catch-22: Transit isn't viable with current density, but we can't densify without good transit. The bind is fractal: One reason given for people needing a car was the lack of grocery stores, but it's illegal to build grocery stores in most single family neighborhoods. Do we need groceries before density, but density before groceries? This is another reason the state needs to step in, and why community feedback on every step is a broken approach. Some of these changes only make sense when done together.

It's also a good cautionary tale for higher government: service cuts reduce trust in future service, and problems become their own argument against trying to fix them. Man, running government is hard.

People don't want to be NIMBYs.

Many people spoke against the plan, but nobody claimed the city shouldn't grow. People explicitly said they weren't NIMBYs, before opposing development in their backyard. They affirmed they wanted affordable housing. They opposed "exclusionary zoning". Nobody arguing against transit corridors said transit was bad. Nobody said it's good their house prices keep going up, because they're rich, and we're not, so screw you.

The average house price in Kirkland is $1.4 Million. If someone bought that average house 30 years ago, paid it off, and let it appreciate, they're a millionaire. Many people mentioned moving here decades ago, and bemoaned threats to neighborhood character. Many talked about how this plan was rushed and could be catastrophic, so we should slow down and think everything through. There's a word for believing things were great decades ago, wanting things to mostly stay the same, and resisting change: Conservative.

If I referred to someone at this meeting as a "conservative, millionaire NIMBY", they would be insulted. I won't be willfully obtuse; they'd be right.

I'm not a millionaire, but I'm not salt of the earth; I have a well-paying tech job. I've lived with roommates in Seattle's Little Saigon and the historically redlined Central District . If someone called me a "rich, white, techie gentrifier", that would also be an insult, and it would be true. It would put me on the defensive. I'd want to explain that "gentrification" is often weaponized to oppose neighborhood improvements, how San Francisco has gentrified despite preserving neighborhoods in amber, how we should upzone wealthier neighborhoods so there's less pressure on Little Saigon… But the point of the epithet is I'm not a credible messenger. It frames me as the problem, doubting my ability to propose a solution besides going away. Calling someone a "conservative millionaire" works the same way, and just as "gentrifier" pokes at my own psychodrama, I suspect "NIMBY" pokes at theirs. Welcome to the central tension of liberal Coastal politics. I think it's encouraging that people are uncomfortable with exclusion, and I don't think it's productive to scream Hypocrisy. We're all hypocrites; the only alternative is having no standards.

If there's reason for optimism, it's that the conversation is changing. I'm hopeful that more pressure from national Democrats will push this conversation in a better direction. Across the street from City Hall, I saw a house with an anti-upzoning sign and a Kamala Harris sign, and I think that stance will become increasingly untenable.

I'll be at the next planning meeting; I still want to fight the good fight. But in the meantime, I'm calling my state representatives.

Epilogue

After the meeting, Cherish Kirkland sent an email to their mailing list, highlighting a strong argument a member had sent to the city. The argument included these excerpts:

All new construction will serve the high-income market. It is impossible to actually build new affordable housing without huge subsidies; costs of land and labor are too high.

The proposed land use plan allows rezoning of an enormous area, 1 mile across and 9 miles long. That is 9 square miles or over 6,000 acres [...] Discounting for parks, current zoning and other geographic limits, we're still talking about 100,000 potential net new units, or a new population of about 250,000, a total of 3.5 times the current population.

Once the city allows such re-zoning, a wave of rezoning requests will overwhelm the community. If the city refuses, a wave of lawsuits will follow. Rezoning at this level in this community is worth a million dollars an acre, which will pay for a lot of lawyers.

How many cities would kill for the chance to unlock $6,000,000,000 of value, attract 250,000 rich residents, and spur tons of local employment? With opposition like this, who needs advocates?